An offshoot of a previous exhibition[1] based on the book Espèces d’espaces (Species of Spaces), by Georges Perec, which proposed an approximation via art of some of the spaces through which the life of man occurs. What particularly caught my attention was that for this French writer, the countryside was nothing other than “the pleasure zone that surrounded the second home of some of his fellow dwellers” and in the same line “the place where one eats homemade bread, breathes better and sometimes sees animals that aren’t normally glimpsed in cities”. If the country has only a few qualities and that as the writer says, "in the country there’s more room than in the city”, seems to be that nothing is as sufficient as considering the country as another of our spaces.

For, according to what Georges Perec says, in reality, the countryside doesn’t exist, it’s an illusion.

I do not know if the countryside is an illusion, and, as such, a distortion of the reality produced by an erroneous interpretation or trick of the senses, or an actual reality and as such an abstraction of the means by which the real, effective existence, of human beings and things, is designated. What I can assure you is that the country is not the same for an urbanite as for a farmer or a shepherd. That is because its significance depends on who is looking at it and how.

To approach the meaning of the country, and, by extension, the meaning of landscape, one has to bear in mind two fundamental concepts; on the one hand, the terrain or territory – that deals with a physical part of the landscape – and on the other, the perception of this terrain, inextricably tied to the subjectivity of he who observes it. Hence why without the existence of a physical space – or territory – and the existence of someone who observes it- perception- the existence of a concept such as landscape would be impossible.

Unlike nature, understood to be a totality, one that doesn’t recognise individuality, a landscape is a delimitation, within man’s field of vision and, as such, a unit of nature perfectly isolated for our gaze. Consequently, it’s a segmented construction, which arises from the relation between nature and the human being – to be more exact, between nature and culture – which leads us to understand landscape as a fragment of nature.

As Javier Maderuelo[2] indicates the landscape is a construction and, as such, doesn’t exist so much as has to be made. Based on this reflection, we could say that more than the contemplated object, that is to say the terrain or territory – the real idea of landscape is found in the gaze of whoever contemplates it – and how they do so. Consequently, the landscape is not what we have in front of us, so much as what is perceived, because it’s a construct, that is to say, a concept that allows us to interpret, culturally and aesthetically, the qualities of a territory, a place, or a lieu.

One of the answers to the question of when, or how, the “new gaze” arises, allowing what lies in front of us to become landscape, indicates it is from the industrial revolution onwards, that is to say between the second half of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century. Up until then, it seems, the ties with the labours of the land were what made the natural surroundings seem to lack any romantic nuances. With the industrial revolution and the exodus of men to the cities, trains appeared. And, the interior of a train offered a new idea of travel and a different vision of the landscape. However, if this perception of the landscape is something new, the concept of it gestates in the history of painting at the beginning of the 15th century, with The Tempest of Giorgione. It stops being a simple background element or scene where the main motive of the picture is represented to become, with the Romantics, the absolute protagonist of painterly representation.

Though there’s been a lot of water under the bridge since then and there are many artists who have contributed their grain of salt, there are many artists today who continue to work with the landscape, working directly from it or a perspective of it. And yes, there are those who spend time on the representation of what they see with total fidelity, just as there are those who find it enough to suggest the idea of it. Far from hinting that what is seen resembles what is actually there, that there is nothing hidden behind the gaze, the pieces by the five artists in this Natural Park, more than anything work from the landscape to assert, insinuate and suggest some of the ideas that speak about all of us. Therefore, more than just a series of works distributed out with or less grace in the interior of a space, what this exhibition proposes is a sort of journey, by train or otherwise, through nature, one that traverses different geographies.

The artists of this exhibition know a lot about imagination, but also about reality, the country, landscape, and illusion. And the reason why they are here is precisely for the illusion of landscape to which they refer, allude, or mirror, that forms their point of departure. That is to say, to breathe life into our Natural Park.

José Ramón Ais (Bilbao,1971)

Trained in Fine Art, with a PhD in Sculpture, and a garden designer, the photographic work of José Ramon Ais is more like a profound journey into what is natural without leaving the domestic garden. For his works, however much they are made in domestic surroundings seem to be made in remote, mythological, or unreal places. Alluding through his photographs to different typologies within the history of gardening – the hortosconclusus, the Zen garden, etc.- or to the different symbolism of flowers, fully evoking a sensorial experience, a garden - Ais invites us to fix our gaze on what we barely ever glimpse. Showing artificial landscapes of vegetation that allow us to glimpse the artificial constructions they become, the works of Ais are a sort of visual composition linked as much to painting as to the origins of photography, ikebana, kitsch landscape calendars, the technologies specific to the image, or special effects in the cinema. Through the use of the chrome key, the dark blue of the sky becomes the backdrop of a setting populated by all sorts of plants: ruderals, adventitious, invasive, productive, wild…each one acting according to its nature, but subject, as in the design of a garden, to the logic of the fiction they represent more than to the scientific rigour of the laws of botany.

Rosa Amorós (Barcelona,1945)

It’s her particular way of connecting with the telluric, the ancestral or the primitive and the questions that accompany them, the myths of creation, religion, being, and our relations with others, that has led Rosa Amorós to be present in this exhibition. With some of the very works in which she manages to transmit a poetics with a more unique and personal look, that is to say, with fired clay. Clay, an ancestral material, that stems from the entrails of the earth, capable of evoking, from beyond, man’s relation with nature, of which her work is an example. Amorós dedicates special attention to nature and the essence of man as tools to think about the force of life, passion, pain, pleasure, and the enigmas of all those emotions provoked by the contemplation of the natural environment.

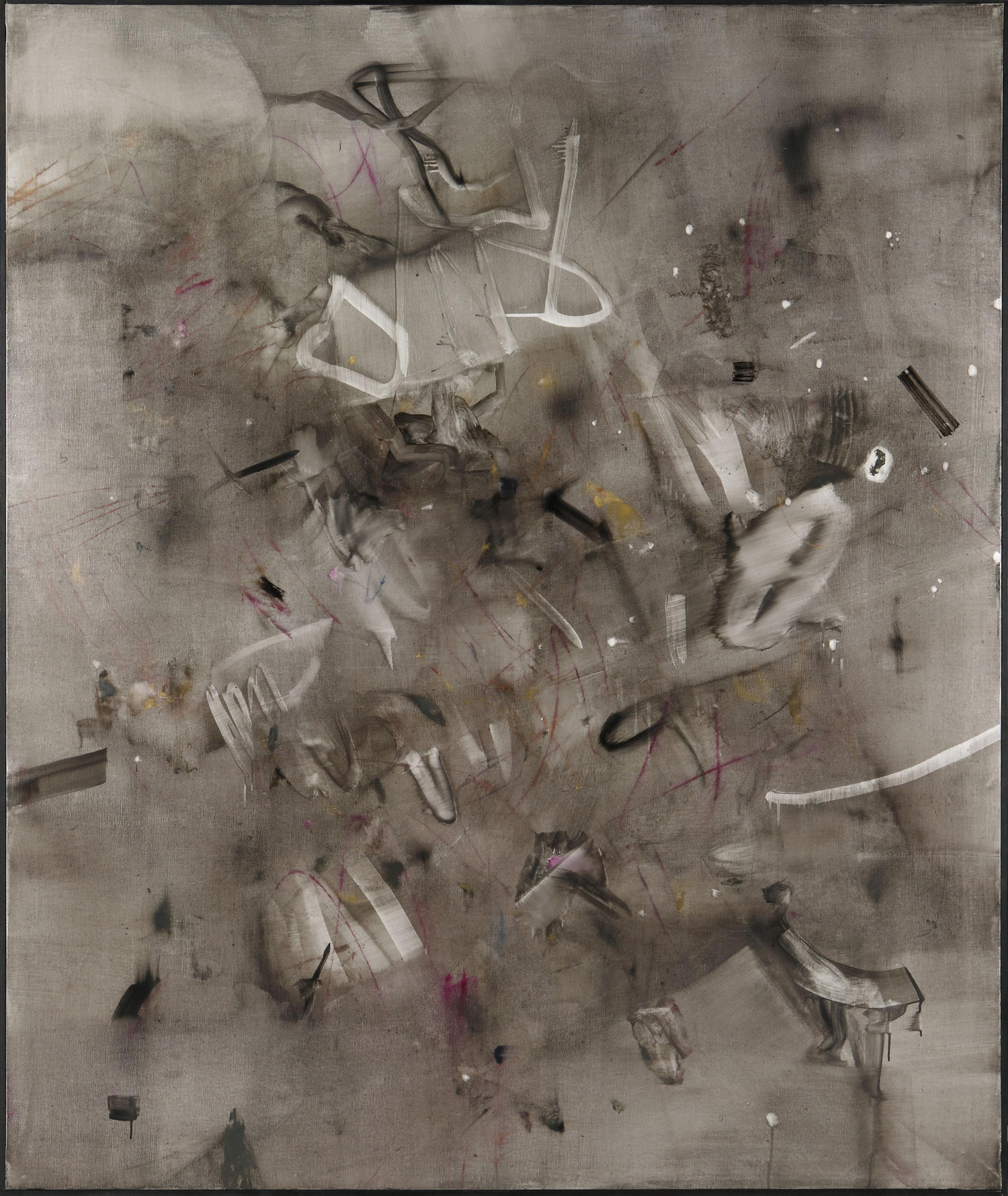

José Díaz (Madrid,1981)

With a degree in Fine Art from the Universidad Complutense of Madrid, José Díaz develops his artistic activity through the medium of paint. Painting understood as a process of investigation, but above all as a way of doing tied particularly to the processes of affect generated through the relation between the human being and the environment. Bringing all these processes of investigation to a practical and visible environment, in a transmission of information in which there are deformation and construction. Díaz’s process centres on the recognition of the form and the consideration of the painterly surface as a surface of data. The surface, such as the one Díaz works upon, condenses the data he perceives when he passes through the city at night, heeding the sounds and understanding that as a painter, his task is rooted in his capacity to translate onto the canvas what would be the landscape and sounds of the city.

Jerónimo Hagerman (Ciudad de México,1967)

For Jerónimo Hagerman, his hobby for plants comes from analysing the relation between the subject and the exterior, and therefore, the emotional tiles between the individual and nature. Debating between the location of what is human in the face of nature and/or the human as part of nature, his work begins documenting the short distance there is, sometimes, between what is artificial and what is natural. A dérive that, over the ten years of his career, has led him to focus his work on his surroundings, man’s ties with vegetation, investigating the different variables in relation to the exterior territory, the landscape, and specifically to the garden as a domestic platform of nature.

Jan Monclús (Lleida,1987)

Monclús’s interest in seeking new ways to tackle figurative painting and his fascination for concepts such as error, chance or failure, shapes the work of this artist obsessed with profiting from the potential of error within the creative process. Based on these considerations, his work, while maintaining a certain debt to the work of Gerhard Richter, Willem Sasnal, Luc Tuymans or RafalBujnowski, is grounded on an investigation into essence, a rejection of ornament and the desire to capture, through brushwork, the world not so much as we see it, so much as an idea of what it could be. A gaze as partial and segmented as that of everyone, but gifted with a unique sense of humour, critical spirit and desire to question the limits of our surroundings.

Curated by Frederic Montornés.

[1]Especies d'espais. Macba. Juliol 2015 - Abril 2016

[2]Maderuelo, Javier. El paisaje. Génesis de un concepto, Abada, Madrid, 2005